Saturday, March 29, 2008

tourisme south sulawesi

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:41 PM 21 comments

Napabale lake ( south east sulawesi)

Napabale Lake in Muna Island is a beautiful virgin lake. The first time I saw it, I thought it was an awesome lake, the best lake I’ve ever seen. It defeats Lake Toba from the top position on my list. Lake Muna is rather tiny compared to Lake Toba. But the water surface of this lake is very beautiful. It reflects light blue color, as those you can see in virgin beaches. Why? Because it is quite shallow (10 m) and actually it is connected to the beach. But the water is not salty. Hm, I was kind of confused with that explanation at first.

Napabale Lake in Muna Island is a beautiful virgin lake. The first time I saw it, I thought it was an awesome lake, the best lake I’ve ever seen. It defeats Lake Toba from the top position on my list. Lake Muna is rather tiny compared to Lake Toba. But the water surface of this lake is very beautiful. It reflects light blue color, as those you can see in virgin beaches. Why? Because it is quite shallow (10 m) and actually it is connected to the beach. But the water is not salty. Hm, I was kind of confused with that explanation at first. There was a tunnel under that wall which connects the lake to the beach. But it was very small. I was so amazed when he started rowing slowly and took us through that tunnel. Ooops, we have to get our head down if we didn’t want to hit the wall. When we’re under the wall, I can touch the wall above my head. That was so cool!! The length of the tunnel is about 20 to 30 m. So, it was quite a stress for my neck. Hehehe…. The view across on the other side of the wall was awesome too. But the fisherman told us that we can’t spend too much time there, because we have to get back soon. If the sea level rose up, the tunnel is gone; water (from the sea) would cover it. And we wouldn’t be able to pass that tunnel. Isn’t it cool? Yeah okay, I know I mentioned “cool” too much. Hehe… Oh yeah, the view at full moon night is also worth waiting for. The reflection of the moon on the water is a perfect accessories for a romantic candle light dinner. :)

There was a tunnel under that wall which connects the lake to the beach. But it was very small. I was so amazed when he started rowing slowly and took us through that tunnel. Ooops, we have to get our head down if we didn’t want to hit the wall. When we’re under the wall, I can touch the wall above my head. That was so cool!! The length of the tunnel is about 20 to 30 m. So, it was quite a stress for my neck. Hehehe…. The view across on the other side of the wall was awesome too. But the fisherman told us that we can’t spend too much time there, because we have to get back soon. If the sea level rose up, the tunnel is gone; water (from the sea) would cover it. And we wouldn’t be able to pass that tunnel. Isn’t it cool? Yeah okay, I know I mentioned “cool” too much. Hehe… Oh yeah, the view at full moon night is also worth waiting for. The reflection of the moon on the water is a perfect accessories for a romantic candle light dinner. :)

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:29 PM 1 comments

Kuta beach..

In the early days of Kuta tourism a few enterprising people set up warungs to serve the growing tourist market. Among the most successful were Made’s Warung (Jl. Pantai Kuta) and Poppies Restaurant (off of Poppies I), both still in business. Another long time favourite is TJ’s (Poppies I), owner Jean starting out with a vegetarian restaurant and moving to Mexican food in 1984.

Kuta is now the center of an extensive tourist-oriented urban area that merges into the neighboring towns. Legian, to the north, is the commercial hub of Kuta and the site of many restaurants and entertainment spots. Most of the area’s big beach-front hotels are in the southern section of Tuban.

Legian and Seminyak are northern extensions of Kuta along Jl. Legian and Jl. Seminyak. They are somewhat quieter suburbs with cottage-style accommodations, where many of the expat crowd live. Also to the north are Petitenget, Berawa, Canggu, and Seseh - new and quieter continuations of Kuta’s beach. They are easy to reach through Abian Timbul or Denpasar and Kerobokan. Several large hotels are located in this area: the Oberoi Bali, Hard Rock Hotel Bali, the Intan Bali Village, the Legian in Petitenget, the Dewata Beach and the Bali Sani Suites in Berawa. To the south, Kuta Beach extends beyond the airport into Jimbaran.

Kuta is just 2 miles from Ngurah Rai airport in Tuban, making it an ideal first night for many visitors. An airport taxi might cost around 25,000rp, dropping you in the Poppies Lane / Benesari area, with a choice of budget / mid-range accommodation.

After the 2002 Sari Club / Paddy’s Bar bombing, Kuta’s nightlife hit the skids. Seminyak seemed to be charging ahead with new bars opening, some of which were conspicuously open at the front, allowing easy escape should there be another bombing. Kuta’s location however meant that was due for a rebound, so with MBarGo, Hook, The Wave, the new Paddy’s, Sky Lounge and other venues, Kuta is a strong contender for nightlife action.

One of the fun ways to check out the neighborhoods in Bali, including Kuta is by using Wikimapia.org. This site allows you to zoom in and out and check out the area. You might spot a few places you’ve been before. Kuta may not look like the French Riviera, but real estate is worth top dollar. In fact most landowners in Kuta will not sell, realizing that times may change, but the location will always mean business. Some long term expats still live in the Tuban, Kuta, Legian area, feeling at home with neighborhood and comfortable living close to the friends they have developed over the years.

Kuta may not be paradise, but it is not the hell hole some travellers make it out to be.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:25 PM 0 comments

Changing your appearance to visit Bali

An article on WorldHum talks about how your appearance will affect your experience while travelling in foreign countries. Particularly a woman asks should she cover up her dreadlocks for a visit to Singapore. There was a time when she would not of been allowed into Singapore with that hairstyle, but times have changed.Bearing in mind that there are 6 billion realities on this planet and we all look different, the bottom line question is ‘how much effort should we invest in trying to look ‘the same’? Society, whichever one you are in, exerts a pressure to normalize, however bizarre it may seem to the newcomer. People generally feel more comfortable with someone who’s reality they can understand, rather than a person operating in his own unique manner.

The dreadlocks into Singapore question was answered with writer Rolf Potts suggesting she should chop her dreadlocks, as locals in Asia would fixate on them, rather than allowing her to interact freely.

In my experience travelling around the world I would say that a ’scummy appearance’ is never appreciated and will attract negative interactions. Having hitch hiked in various countries I have had people offer rides, who have told me they never pick up hitch hikers, but did for me because I look ‘clean’ (not a vagrant / drug user, threatening). I think my answer to the hair question would be whatever your style, you want to project something positive. For more conservative countries, that may require cutting back on the tie-dye outfits and dreadlocks and relating to the locals visually in a manner they are more familiar with.

How does that relate to Bali? Tourists have been coming to mass in large numbers since the 1970’s. Locals have adapted to the international array of people who arrive here and probably more accepting of different styles than in most other places in the world. Still, if you visit a temple you should wear the appropriate attire. When visiting a government office, smart plain clothes are a good idea, in fact the Indonesian Embassy in Singapore will not allow you in without long pants.

Restaurants and nightclubs in Bali do not have a dress-code, so no one is going to give you a hard time about the way you look. The hot weather in Bali means you cannot realistically force people to wear long pants and a jacket, so no nobody does.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:19 PM 0 comments

CULTURE AND TOURISM OF CENTRAL SULAWESI

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:17 PM 0 comments

travel agent in south sulawesi

RANTEPAO

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:14 PM 0 comments

Natural Resource South East Sulawesi Province

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:13 PM 0 comments

Travel agent south east sulawesi

PT. Bokori Inter NusaDrs. H. Abdullah Silondae Stret,Kendari

PT. Alam JayaDr. Ratulangi Street, KendariPhone: (0401) 21729

PT. Manorian Mega StarSultan Hasanuddin Street, Kendari

PT. Wollo Tour & TravelButon Barat Street 2, Bau-BauPhone: (0402) 21187

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:11 PM 0 comments

Travel agent in west papua

Makmur Thomas TravelA. Yani Street 1/14, SorongPhone: (0967) 3 3593

Cahaya Alam AgungKota Baru Street 39, ManokwariPhone: (0962) 21153, 21133

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:04 PM 0 comments

NORTH SULAWESI PROVINCE

Travel agent in manado

Pandu Express Tours & TravelSam Ratulangi Street 91, ManadoPhone: (0431) 854033

Pola Pelita Express Tours & TravelSam Ratulangi Street 133, ManadoPhone: (0431) 859303

Dian Sakato Tours & TravelSama Ratulangi Street 1, ManadoPhone: (0431) 860003

Winamulia JayaSarapung Street 5, ManadoPhone: (0431) 854912

Graniesko Sutara LeisureMartadinata Street 50, ManadoPhone: (0431) 857700

Oespindo Sulut IndahSam Ratulangi Street 40, ManadoPhone: (0431) 851342

Vita International Tours & TravelSam Ratulangi Street 83, ManadoPhone: (0431) 851342

Tojosin Cipta PesonaSam Ratulangi Street 29, ManadoPhone: (0431) 858411

Bumi Nata Wisata ToursSam Ratulangi Street II 61, ManadoPhone: (0431) 841170

Limbunan Tours & TravelSam Ratulangi Street 159, ManadoPhone: (0431) 857555

Klabat Wisata Utama TravelWalanda Maramis Street 196, ManadoPhone: (0431) 867646

Bumi Beringin Wisata17 Agustus Street, ManadoPhone: (0431) 861852

Metropole Devra ExpressSudirman Street 135, ManadoPhone: (0431) 851333

Maya ExpressSudirman Street 15, ManadoPhone: (0431) 870111

Alexander DinamikaSutomo Street 12A, ManadoPhone: (0431) 86880

Duta Sulut RayaSam Ratulangi Street 30, ManadoPhone: (0431) 853505

Trampil Tours & TravelWalanda Maramis Street 1, ManadoPhone: (0431) 852222

Dembean Express Tours & TravelSudirman Street 3, ManadoPhone: (0431) 854029

Rahmat Sinar NusantaraSudirman Street 109, ManadoPhone: (0431) 859600

Steps Tour & TravelLumimuut Street 4, ManadoPhone: (0431) 850572

Vytinyendi Tours & TravelSudirman Street 124, ManadoPhone: (0431) 867146

Riantama Tours & TravelHasanudin 63 Street, ManadoPhone: (0431) 862322

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 2:00 PM 0 comments

Qunci Villa Senggigi: Mangsit street - Senggigi - Lombok

Areas served:

Mangsit street - Senggigi - Lombok

Rate information:

All rates indicated are for search purposes only; check availability to verify rate.

Recreation info:

nits on a beautifully landscaped beachfront property peppered with swaying palms and lush tropical plants. The Villas are a tasteful mixture of modern architecture combined with the architectural style of Lombok and Bali. Designed by Joost Van Grieken, the renowned Dutch architect residing in Bali,Qunci Villas is specifically designed to take full advantage of the stunning views across the exotic gardens out across the sparkling blue waters of the Lombok Straits.

Restaurant:

American meal plan

Meeting facility:

None

Registration time:

check in 2300, check out 2300

Address:

83010 Mangsit Street-Senggigi-Lombok, Senggigi, Indonesia

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:58 PM 0 comments

Social and Cultural South East Sulawesi province

South East Sulawesi has several group of area language with different dialect. The difference of this dialect enrich Indonesian culture treasure. The group of area language in South East Sulawesi and each dialect are:

Tolaki language group stand for: Mekongga dialect, Konawe dialect, Moronene dialect, Wawonii dialect, Kulisusu dialect, Kabaena dialect;

Muna language group stand for: Tiworo dialect, Mawasangka dialect, Gu dialect, Katobengke dialect, Siompu dialect, Kadatua dialect;

Pongana language group stand for: Lasalimu dialect, Kapontori dialect, Kaisabu dialect;

Walio (Buton) language group stand for: Kraton dialect, Pesisir dialect, Bungi dialect, Tolandona dialect, Talaga dialect;

Cia-Cia language group stand for: Wobula dialect, Batauga dialect, Sampolawa dialect, Lapero dialect, Takimpo dialect, Kandawa dialect, Halimambo dialect, Batuatas dialect, Wali dialect (in Binongko island);

Suai language group stand for: Wanci dialect, Kaledupa dialect, Tomia dialect, Binongko dialect. To arrange life connection among community there is a custom law is always obeyed by community. The kind of custom law that is land law, community intercourse law, married law and heir law. South East Sulawesi has many kinds of potential arts that enrich the Indonesian culture treasure. The kinds of arts are dance art, carved art, paint art, sing art and sound art. The dance art constitute community dance who are performed at every traditional ceremony or welcome high guests to be accompanied by traditional music tools like gong, kecapi, and bamboo flute blowing besides modern music kinds of dance art in Central Sulawesi are: Umoara dance, Mowindahako dance, Molulo dance, Ore-Ore dance, Linda dance, Dimba-Dimba dance, Moide-Moide dance, Honari dance. Besides that South East Sulawesi well known also with Carved art that is Silver carved where as the others carved art are rattan plait and gembol table from wood.Source: Indonesia Tanah Airku (2007).

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:57 PM 0 comments

Some 300 British tourists to visit Ambon

At least 300 British tourists aboard `Sagarose` cruise ship were expected to visit Maluku province`s capital of Ambon next March 3, 2008, a local official has said.

var gaJsHost = (("https:" == document.location.protocol) ? "https://ssl." : "http://www."); document.write(unescape("%3Cscript src='" + gaJsHost + "google-analytics.com/ga.js' type='text/javascript'%3E%3C/script%3E"));

var pageTracker = _gat._getTracker("UA-3529100-1"); pageTracker._initData(); pageTracker._trackPageview();

counter('1203564610','2008_02','en','http://www.antara.co.id'); /*cyear('year');*/

"Some 300 British tourists are scheduled to stay in Ambon for about eight hours to visit a number of tourist objects and enjoy Maluku`s special arts attractions," Spokesman for the Ambon city administration, Henry Sopacua, said here Thursday. Preparations have been made jointly with Maluku province`s Tourism Office, local security authorities, immigration office, state shipping company PT Pelni and local port administrator to welcome the foreign visitors. Various preparations have also been made in support of the Visit Indonesia 2008 program, he said. The British tourists were slated to visit the cemetery of Commonwealth soldiers who were killed during the World War II in Kapahaha area, Natsepa beach, Liang beach and Eel tourist site in Waai village. The British tourists were also expected to enjoy the view of Ambon City where they can see the statue of national heroin Martha Christina Tiahahu in Karang Panjang area and Mt. Nona."Under the directives from Ambon Mayor Jopi Papilaja who has the idea of inviting the 300 British tourists, we are also preparing an arts collaboration performance dubbed `Tatobuang` and `Sawat`," Henry said. Head of Maluku province`s tourism office, Ape Watratan, hinted that Maluku Governor Karel Albert Ralahalu has included the visit of the 300 British tourists in the provincial tourism program in support of the Visit Indonesia 2008. "The number of foreign tourists coming to Maluku continues to rise thanks to the increasingly conducive security situation following the communal conflict which began in 1999 but has now ended in peace," Ape said. Tourists from Australia have even frequently visited Maluku despite a travel warning issued by their government, he said. (*)

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:52 PM 0 comments

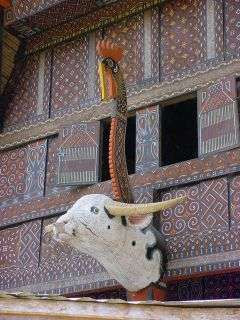

aerial views" THE TONGKONAN OF TORAJA (soutt sulawesi)

Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until the beginning of the past millenium. Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughly 70% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until the beginning of the past millenium. Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughly 70% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

Tongkonan are built on wooden piles. They have saddleback roofs whose gables sweep up at an even more exaggerated pitch than those of the Toba Batak. Traditionally, the roof is constructed with layered bamboo, and the wooden structure of the house assembled in tongue-and-groove fashion without nails. Nowadays, of course, zinc roofs and nails are used increasingly. The construction of a traditional house is time-consuming and complex, and requires the employment of skilled craftsmen. First of all, seasoned timber is collected, then a shed of bamboo scaffolding with a bamboo shingle roof is erected. Here, components of the house are prefabricated, though the final assembly will take place at the actual site. Almost invariably now, tongkonan are raised on vertical piles rather than on a substructure of the log-cabin type, so all the wooden piles are shaped and morrises cut in them to take the horizontal tie beams. The piles are notched at the top to accommodate the longitudinal and transverse beams of the upper structure. The substucture is then assembled at the final site. Next, the transverse beams are fitted into the piles, then notched and the longitudinal beams set into them, and the grooved uprights that will form the frame for the side walls are pegged in place. Thin side panels are cut to the dimensions decided on by the woodcarver who is going to decorate them, and slotted in, The two outermost uprights of each transverse wall pass through the upper horizontal wall beam and, being forked at the upper end, carry the parallel horizontal beams that support the rafters. A narrow hardwood post, also forked at the top and set into the central longitudinal floor beam, runs up each transverse wall, is anchored to the upper wall beam and carries the ridge purlin. The rafters are laid over the ridge purlin, whose extended ends rest on the triangular overhanging gables. An upper ridge pole is then laid in the crosses formed by the rafters, and the ridge pole and ridge purlin lashed together with rattan.

To obtain the increasingly curved roof so popular with the Toraja, the ends of the upper ridge pole must be slotted through the centres of short vertical hanging spars, whose upper halves support the first of the upwardly angled beams at the front and rear of the house, which in turn slots through the centre of further short vertical hanging spars that carry the second upwardly angled beam. The sections of the ridge pole projecting beyond the ridge purlin are supported front and back by a freestanding pole. Transverse ties pass through both the hanging spars and the freestanding posts to support the rafters of the projecting roof. Before the roof is fitted, stones are placed under the piles. The roof is made of bamboo staves bound together with rattan and assembled transversely in layers over an under-roof of bamboo poles, which are tied longitudinally to the rafters. Flooring is of wooden boards laid over thin hardwood joists. Toraja society is extremely hierarchical, comprising nobility, commoners and a lower class who were formerly slaves. Villagers are only permitted to decor their house with the symbols and motifs appropriate to their social station. The gables and the wooden wall panels are incized with geometric, spiralling designs and motifs such as buffalo heads and cockerels painted in red, white, yellow and black, the colours that represent the various festivals of Aluk To Dolo ('the Way of the Ancestors'), the indigenous Toraja religion. Black symbolizes death and darkness; yellow, God's blessing and power; white, the colour of flesh and bone, means purity; and red, the colour of blood, symbolizes human life. The pigments used were of readily available materials, soot for black, lime for white and coloured earth for red and yellow; tuak (palm wine) was used to strengthen the colours. The artists who decorated the house were traditionally paid with buffalo. The majority of the carvings on Toraja houses and granaries signify prosperity and fertility, and the motifs used are those important to the owner's family. Circular motifs represent the sun, the symbol of power, a golden keris (knife) symbolizes wealth and buffalo heads stand for prosperity and ritual sacrifice. Many of the designs are associated with water, which in itself symbolizes life, fertility and prolific rice fields. Tadpoles and water-weeds, both of which breed rapidly, represent hopes for many children. Many of the motifs that adorn the houses and granaries of the Toraja are identical to those found on the bronze kettle drums of the Dong-Son. Others, such as the square cross motif, are thought to have Hindu-Buddhist origins or to have been copied from Indian trade cloths. The cross is used by the Christian Toraja as a decorative design emblematic of their faith. On the front wall of the most important houses of origin is mounted a realistically carved wooden buffalo head, adorned with actual horns. This emblem may only be added to the house after one of the most important funeral rites has been celebrated.

To the Toraja, the tongkonan is more than just a structure. The symbol of family identity and tradition, representing all the descendants of a founding ancestor, it is the focus of ritual life. It forms the most important nexus within the web of kinship. Toraja's may have difficulty defining their exact relationship to distant kind, but can always name the natal houses of parents, grandparents and sometimes distant ancestors, for they consider themselves to be related through these houses. Descent amongst the Toraja is traced bilaterally - that is, through both the male and female line. People therefore belong to more than one house. Membership of these houses only requires the kinsman's active participation at times of ceremony, the division of an inheritance or when a house is rebuilt. Although the tongkonan has become identified by outsiders as being representative of all Toraja buildings, it is only the nobility and their descendants who can afford both the building of the houses themselves and the enormous ritual feasts associated with them. Noble Toraja can claim affiliation to a particular tongkonan as descendants of the founding ancestor, through the male or female line. This association is periodically confirmed through contributions to the ceremonial feasts given by the tongkonan household. Commoners customarily lived in smaller, simpler houses and acted as helpers at these communal feasts. Commoners trace their descent through their own houses of origin. These, although of simpler design and decoration, may still be known as tongkonan. As in so many places in modern Indonesia, the traditional house, with its cramped, dark, smoky interior, has lost its attraction for many Toraja (although it still commands great ritual prestige). Many have opted for a ground-built, concrete, single-storey house in the contemporary Pan-Indonesian style, and some have adopted a wooden, pile-built dwelling. Others who are more inclined towards tradition may add an extra storey and a saddleback roof; this provides more living space and room for furniture whilst retaining something of the prestige the tongkonan affords its owner. Contemporary Toraja buildings are thus the result of architectonic development which has diminished their value as dwellings. In so doing, they have employed new technology to further emphasize the traditional philosophy of the Toraja. The basic plan has remained virtually constant throughout the changes, and the importance of its underlying notions of culture, religion, and society has guided the direction of the tongkonan's evolvement. So close have the lines of change stayed to these fundamental concepts, that the process has been labeled an "involution". Despite the modernity of the new tongkonan, it has succeeded in maintaining its richness of intertwined symbolism and continues to resonate with deep cultural meaning.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:42 PM 0 comments

event in this years "2008

SKY GLIDING CHAMPIONSHIPAgam, West Sumatera, May 2008SKY GLIDING FESTIVALKota Batu, East Java, May 2008EAST NUSA TENGGARA CULTURAL FESTIVALEast Nusa Tenggara, May 2008GRAND PRIX PHINISIJakarta, May 20 - August 17, 2008This event will be followed by 200 phinisi boats acrossing 5,000 miles of distance from Sabang to Merauke. Through 90 days of adventures, all the participants will have the glorious experience from the graceful phinisi.

KITE FESTIVAL PANGANDARANCiamis, West Java, July 17-19, 2008CANDI CETHO FESTIVALTawangmangu, Karanganyar, Central Java July 17, 2008TOGIAN FESTIVALKab.Tojouna-Una, Central Sulawesi July 23-27, 2008DARWIN AMBON SAIL RACEAmbon, Maluku, July 2008LAKE KERINCI CULTURAL FESTIVAL (2ND WEEK)Jambi July 2008SENGGIGI FESTIVALSenggigi, Lombok,West Nusa Tenggara July 2008THE INTERNATIONAL INDONESIA MOTOR SHOW(IIMS) Jakarta, July 2008FIM WORLD SBK CHAMPIONSHIPSirkuit Sentul, Bogor West Java, July 19-20, 2008KEMILAU SULAWESI (2ND WEEK)Gorontalo, July 2008

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:29 PM 1 comments

Early Agriculture and Lake Margins

Tree under which the Treaty of Wajoq was agreed

Tree under which the Treaty of Wajoq was agreedAt Malangke in Luwu, a team from Balai Arkaeologi Makassar led by Budianto Hakim excavated what they believe to have been a Javanese-style brick structure dating to the fourteenth century AD. Unfortunately, the research was inconclusive as the site had been thoroughly looted, leaving only a scatter of bricks.

In July, Ian Caldwell, Stephen Druce and Budianto Hakim visited Wajo, where they found that the tree under which the treaty of that formed the kingdom under the leadership of the fourth Arung Matowa, La Tadampareq, Puang Magalatung has fallen down. Its surrounding fence is in disrepair and the enclosure in which the tree stood is overgrown with secondary forest.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:22 PM 0 comments

‘The Palace on the Hill Ridge’

Allangkanangngé ri La Tanété, ‘The palace on the hill ridge’, is one of the most important historical sites in South Sulawesi. The low hill lies at the heart of the Bugis speaking region, a few kilometers east of the great lakes. The summit of the hill is held to have been the palace centre of an early Bugis kingdom called Cina (pronounced Chee-na).

Allangkanangngé ri La Tanété, ‘The palace on the hill ridge’, is one of the most important historical sites in South Sulawesi. The low hill lies at the heart of the Bugis speaking region, a few kilometers east of the great lakes. The summit of the hill is held to have been the palace centre of an early Bugis kingdom called Cina (pronounced Chee-na). Cina is not found in the historical records of South Sulawesi other than as a source of status for the rulers of historically later kingdoms. This suggests that Cina had declined or disappeared before the development of writing around 1400. The kingdom does, however, figure prominently in the Bugis poetic epic La Galigo, which is believed by many scholars to retain a memory of a distant past.

The hill was first examined by Kaharuddin in his undergraduate thesis in 1994. In August 1999, an OXIS team led by Dr Ali Fadillah carried out a survey of the summit of the hill and opened a one by one metre test pit on the raised earth platform which lies on the broadest part of the summit ridge. Time constraints meant the abandonment of the test pit before reaching sterile earth.

In June and July 2005, an OXIS Group team comprising Ian Caldwell, Stephen Druce, Budianto Hakim and Campbell Macknight, with Pak Mansur as surveyor, carried out a full theodolite survey and surrface collection of the hill. The team reopened the 1999 test pit and excavated down to sterile earth. Two other 1 x 1 metre test pits, were excavated alongside the first test pit and revealed a similar stratigraphy,. Clear evidence of the forest floor was found at a depth of 0.8 m in the form of light brown soil. Charcoal found just above this layer was AMS dated at the Waikato laboratory to 1215-1290 CE with 95.4% probability. This is the earliest date yet recorded for what appears to be an early rice-based Bugis kingdom.

Research was funded by the British Academy Committee for South East Asian Studies.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 1:05 PM 0 comments

travel to sulawesi: Languages and Peoples of South Sulawesi

The languages spoken in South Sulawesi belong to one of four stocks of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family; namely, the South Sulawesi stock, the Central Sulawesi stock, the Muna-Buton stock and the Sama-Bajaw stock. Speakers of Muna-Buton stock languages inhabit the area of Wotu in Luwu Utara, the southern tip of Selayar island and the small islands of Kalao, Bonerate, Kalaotoa and Karompa, all of which are located to the southeast of Selayar. Speakers of Central Sulawesi stock languages inhabit the northern half of kabupaten (regency) Mamuju and the northern and eastern parts of kabupaten Luwu Utara. Sama-Bajaw speakers are scattered in a few coastal areas of Bone and Luwu and around the islands of Selayar and Pangkep. Here I will focus only on those languages that make up the South Sulawesi language group, which are spoken by the vast majority of the province’s inhabitants.

The languages spoken in South Sulawesi belong to one of four stocks of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family; namely, the South Sulawesi stock, the Central Sulawesi stock, the Muna-Buton stock and the Sama-Bajaw stock. Speakers of Muna-Buton stock languages inhabit the area of Wotu in Luwu Utara, the southern tip of Selayar island and the small islands of Kalao, Bonerate, Kalaotoa and Karompa, all of which are located to the southeast of Selayar. Speakers of Central Sulawesi stock languages inhabit the northern half of kabupaten (regency) Mamuju and the northern and eastern parts of kabupaten Luwu Utara. Sama-Bajaw speakers are scattered in a few coastal areas of Bone and Luwu and around the islands of Selayar and Pangkep. Here I will focus only on those languages that make up the South Sulawesi language group, which are spoken by the vast majority of the province’s inhabitants.Grimes and Grimes (1987) tentatively identified about 20 distinct languages of the South Sulawesi stock, which they placed into 10 related family or subfamily groupings. Friberg and Laskowske (1989) revised this identification to 28 distinct languages within 8 family or subfamily groupings. A further revision by Grimes (2000) now identifies 29 distinct languages within 8 family or subfamily groupings.

(1) The Bugis family, which consists of two languages: Bugis (3,500,000 speakers) and

Campalagian (30,000 speakers)

(2) The Lemolang language (2,000 speakers)

(3) The Makasar family, which consists of five languages: Bentong (25,000 speakers)

Coastal Konjo (125,000 speakers), Highland Konjo (150,000 speakers), Makasar

(1,600,000 speakers) and Selayar (90,000 speakers)

(4) The Northern South Sulawesi family, which consists of two languages, Mandar (200,000

speakers) and Mamuju (60,000 speakers), and three subfamilies (below, 5, 6 & 7)

(5) The Massenrempulu subfamily, which consists of four languages: Duri (95,000

speakers), Enrekang (50,000 speakers), Maiwa (50,000 speakers) and Malimpung

(5,000 speakers)

(6) The Pitu Ulunna Salu subfamily, which consists of five languages: Aralle-Tabulahan

(12,000 speakers), Bambam (22,000 speakers), Dakka (1,500 speakers), Pannei (9,000

speakers) and Ulumandaq (30,000 speakers)

(7) The Toraja-Saddan subfamily, which consists of six languages: Kalumpang (12,000

speakers), Mamasa (100,000 speakers), Taeq (250,000 speakers), Talondoq (500

speakers), Toalaq (30,000 speakers) and Toraja-Saddan (500,000 speakers)

(8) The Seko family, which consists of four languages: Budong-Budong (70 speakers)

Panasuan (900 speakers), Seko-Padang (5,000 speakers) and Seko-Tengah (2,500

speakers)

The spatial distribution of these languages is shown on the following webpage.

The most convergent of the 29 languages are those that make up the Northern South Sulawesi family. These have lexical similarities with one another ranging from 52 per cent to 72 per cent (Grimes and Grimes 1987:19). The Bugis family shares a relatively high percentage of lexicostatistical similarities with the Northern South Sulawesi family languages, averaging over 52 per cent. The most divergent of the South Sulawesi languages are those that make up the Makasar family, sharing an average of just 43 per cent lexical similarity with the other members of the South Sulawesi stock (Grimes and Grimes 1987:25). Earlier linguistic work by Mills (1975:491) also shows Makasar languages to be the most distinct of the South Sulawesi languages. Both Mills and Grimes and Grimes (1987:25) conclude that Makasar was the first language to break off from the Proto South Sulawesi language. At the same time, there is also significant divergence within the Makasar family itself: the Makasar language shares 75 per cent, 76 per cent and 69 per cent lexical similarities with Highland Konjo, Coastal Konjo and Selayar respectively (Grimes 2000).

How many of the 29 South Sulawesi stock languages are today commensurate to individual ethnic groups is uncertain, as to date no studies have addressed local ethnic perceptions in any detail. Much academic and most tourist literature mentions only the four largest of South Sulawesi’s ethnic groups, the Bugis, Makasar, Saddan-Toraja and Mandar. Smaller groups are either ignored or considered to belong to one of the four ethnic groups above, which stands in opposition to local ethnolinguistic perceptions. From a historical and archaeological perspective, the linguistic data can be considered as a basic guide to understanding ethnic diversity and ethnic boundaries in South Sulawesi.

The most numerous ethnic group of South Sulawesi are the Bugis, who number about 3,500,000. The Bugis occupy most of the eastern half of the peninsula, much of the western half of the peninsula (from around kabupaten Pangkep to the central-northern parts of kabupaten Pinrang and Sidrap, all of the central fertile plains, and parts of the coastal plain in kabupaten Luwu. Small pockets of Bugis are also found in kabupaten Luwu Utara, Polmas and Mamuju. Next largest numerically are speakers of Makasar languages, about 1,600,000 of whom inhabit the southwestern part of the peninsula, most of the peninsula’s southern coast and all but the southern tip of Selayar island. With the exception of the fertile area in the southwestern part of the province and the area around Maros, the Makasar occupy less fertile land than the Bugis and are consequently less prosperous.

The Bugis and Makasar peoples are often stereotyped as sailors, traders, and even occasionally as pirates. While some are indeed traders and sailors this stereotypical image has been created from the activities of a relatively small number of individuals. This reputation appears to date to no earlier than the seventeenth century (see Lineton 1975:177-185; Abu Hamid 1987:2-17). The reality is that the Bugis and Makasar are primarily farmers, whose main occupation for centuries has been intensive wet-rice cultivation together with other minor crops. Indeed, the emergence of the Bugis and Makasar kingdoms after 1300 was directly linked to the expansion of wet-rice agriculture (Macknight 1983).

The Bugis and Makasar are often considered the most closely related of South Sulawesi’s ethnic groups, despite the evident linguistic divergence. Some local scholars even use the compound term ‘Bugis-Makasar’ when writing about South Sulawesi culture and history. While there are common cultural traits between these two ethnic groups, the term ‘Bugis-Makasar’ appears to have been born, at least in part, from a desire for a common Islamic identity. Today, Islam is an important expression of ethnic identity for both ethnic groups, yet as Friberg and Laskowske (1989:3) note, where Bugis and Makasar languages overlap in kabupaten Maros and Pangkep, each language remains distinct, and individuals clearly identify themselves as either Bugis or Makasar. At the same time, Bugis and Makasar genres of indigenous writings closely correspond with each other, as do their oral traditions, and from about 1300 onwards the two ethnic groups shared similar historical experiences.

Another ethnic group often associated with the Bugis and Makasar are the Mandar who also converted to Islam at the beginning of the seventeenth century. About 200,000 Mandar-speakers inhabit the narrow coastal strip and hill areas in the northwestern part of the peninsula in kabupaten Majene and Polmas. Of all the peoples of South Sulawesi, it is the Mandar whose life is most closely linked to the sea. Their main occupation is fishing but they also cultivate cacao, copra, maize and cassava.

Speakers of Toraja-Saddan languages total about 890,000. They are spread over a relatively wide area in the northern half of the province. The majority inhabit kabupaten Tana Toraja and are often referred to as the Saddan-Toraja, after the name of the river that flows through the region. The Saddan-Toraja began to convert to Christianity in the early part of the twentieth century as a result of the work of Dutch missionaries. Today, about 87 per cent are Christian and 9 per cent are Muslim, with the remainder still following the indigenous religion known as aluq to dolo, ‘way of the ancestors.’ (Waterson 1990:111). While wet-rice is grown in river valleys, the Saddan-Toraja mainly practice garden cultivation, the most lucrative crop being coffee.

To the east of the Saddan-Toraja in kabupaten Polmas are speakers of the Mamasa language, often called the Mamasa-Toraja. As with the Saddan-Toraja most of the Mamasa-Toraja are Christian. Despite this, both the Mamasa-Toraja and Saddan-Toraja consider themselves to be ethnically and culturally distinct to one another, this being evident in their complicated architecture, and for the Mamasa-Toraja the absence of the famous cliff-face graves of Tana Toraja.

Speakers of Toraja-Saddan languages also inhabit large areas of kabupaten Luwu and Luwu Utara, where they make up at least one third of the population. Small pockets of Toraja-Saddan speakers also inhabit the northern tip of kabupaten Pinrang and the southeastern part of Mamuju. The majority Taeq and Toalaq speakers of Luwu and Luwu Utara are Muslim, which tends to exaggerate differences between them and their Saddan-Toraja neighbours.

Massenrempulu-speaking ethnic groups collectively number about 200,000. They occupy the low hills and mountain areas in kabupaten Enrekang, and the northern parts of kabupaten Pinrang and Sidrap, the area between the Bugis and Saddan-Toraja. Most speakers of Massenrempulu languages converted to Islam in the seventeenth century. Partly because of a shared Islamic identity, the Massenrempulu are often associated with their Bugis neighbours. However, Massenrempulu-speaking groups claim to be ethnically distinct from the Bugis and also from one another (see Druce 2005). Although some wet-rice is grown, most Massenrempulu practice garden cultivation.

Speakers of Pitu-Uluna-Salo languages number about 74,000 and inhabit the hill and mountain areas to the north and east of kabupaten Mandar, with whose people they have had a long economic and cultural relationship (George 1996). The majority of Pitu-Uluna-Salo-speakers are now Muslim but there is a sizeable Christian minority. As with speakers of Toraja-Saddan languages, the religious divergence of Pitu-Uluna-Salo-speakers has created divisions, as some of the Muslim majority have begun to develop a greater affinity with their Mandar neighbours.

The 60,000-odd speakers of the Mamuju language inhabit the coastal plain and foothills in the most northerly part of the South Sulawesi province, where they practice garden cultivation and fishing. To the south and southeast are about 4,000 speakers of Seko languages, who inhabit the rugged terrain in central areas of kabupaten Mamuju and Luwu Utara.

One of the smallest ethnic group that speaks a South Sulawesi stock language is the Lemolang. About 2,000 people living in the foothills around Baebunta and Sabbang in Luwu Utara speak this language. While the small number of speakers suggests that Lemolang is in danger of disappearing, Grimes (2000) reports that of 25 children questioned in 1990, 76 per cent said that they spoke the language well.

In spite of the evident cultural, religious and ethnic diversity, there are a number of cultural concepts shared by all South Sulawesi group speakers reflect which point a common origin. These include the importance given to ascriptive status, the position of women as status markers for a kin group, the concept of siriq (self-worth, shame) and the concept of a white-blooded ruling elite, many of whom are believed to be descended from tomanurung (beings descended from the Upperworld to rule over the common people) or totompoq (beings who arose from the Underworld). While there are significant differences in architecture, the traditional houses of all South Sulawesi language speakers have a central post around which house ceremonies are conducted, and houses are traditionally built facing north.

Posted by Hotel Bali Indonesia at 12:05 PM 2 comments