Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until the beginning of the past millenium. Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughly 70% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

Toraja is a name of Bugis origin given to the different peoples of the mountainous regions of the northern part of the south peninsula, which have remained isolated until the beginning of the past millenium. Their native religion is megalithic and animistic, and is characterized by animal sacrifices, ostentatious funeral rites and huge communal feasts. The Toraja only began to lose faith in their religion after 1909, when Protestant missionaries arrived in the wake of the Dutch colonizers. Nowadays roughly 70% of the Toraja are Christian, and 10% are Muslim; the rest hold in some measure to their original religion. Whatever their religious belief, it is their ancestral home, their 'house of origin', the great banua Toraja with its saddleback roof and dramatically upswept roof ridge ends, that is the cultural focus for every Toraja. This house of origin is also known as a tongkonan, a name derived from the Toraja word for 'to sit'; it literally means the place where family members meet - to discuss important affairs, to take part in ceremonies and to make arrangements for the refurbishment of the house.

Tongkonan are built on wooden piles. They have saddleback roofs whose gables sweep up at an even more exaggerated pitch than those of the Toba Batak. Traditionally, the roof is constructed with layered bamboo, and the wooden structure of the house assembled in tongue-and-groove fashion without nails. Nowadays, of course, zinc roofs and nails are used increasingly. The construction of a traditional house is time-consuming and complex, and requires the employment of skilled craftsmen. First of all, seasoned timber is collected, then a shed of bamboo scaffolding with a bamboo shingle roof is erected. Here, components of the house are prefabricated, though the final assembly will take place at the actual site. Almost invariably now, tongkonan are raised on vertical piles rather than on a substructure of the log-cabin type, so all the wooden piles are shaped and morrises cut in them to take the horizontal tie beams. The piles are notched at the top to accommodate the longitudinal and transverse beams of the upper structure. The substucture is then assembled at the final site. Next, the transverse beams are fitted into the piles, then notched and the longitudinal beams set into them, and the grooved uprights that will form the frame for the side walls are pegged in place. Thin side panels are cut to the dimensions decided on by the woodcarver who is going to decorate them, and slotted in, The two outermost uprights of each transverse wall pass through the upper horizontal wall beam and, being forked at the upper end, carry the parallel horizontal beams that support the rafters. A narrow hardwood post, also forked at the top and set into the central longitudinal floor beam, runs up each transverse wall, is anchored to the upper wall beam and carries the ridge purlin. The rafters are laid over the ridge purlin, whose extended ends rest on the triangular overhanging gables. An upper ridge pole is then laid in the crosses formed by the rafters, and the ridge pole and ridge purlin lashed together with rattan.

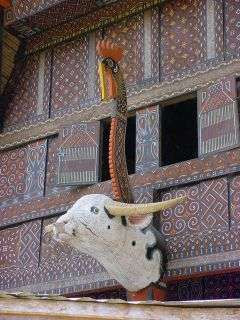

To obtain the increasingly curved roof so popular with the Toraja, the ends of the upper ridge pole must be slotted through the centres of short vertical hanging spars, whose upper halves support the first of the upwardly angled beams at the front and rear of the house, which in turn slots through the centre of further short vertical hanging spars that carry the second upwardly angled beam. The sections of the ridge pole projecting beyond the ridge purlin are supported front and back by a freestanding pole. Transverse ties pass through both the hanging spars and the freestanding posts to support the rafters of the projecting roof. Before the roof is fitted, stones are placed under the piles. The roof is made of bamboo staves bound together with rattan and assembled transversely in layers over an under-roof of bamboo poles, which are tied longitudinally to the rafters. Flooring is of wooden boards laid over thin hardwood joists. Toraja society is extremely hierarchical, comprising nobility, commoners and a lower class who were formerly slaves. Villagers are only permitted to decor their house with the symbols and motifs appropriate to their social station. The gables and the wooden wall panels are incized with geometric, spiralling designs and motifs such as buffalo heads and cockerels painted in red, white, yellow and black, the colours that represent the various festivals of Aluk To Dolo ('the Way of the Ancestors'), the indigenous Toraja religion. Black symbolizes death and darkness; yellow, God's blessing and power; white, the colour of flesh and bone, means purity; and red, the colour of blood, symbolizes human life. The pigments used were of readily available materials, soot for black, lime for white and coloured earth for red and yellow; tuak (palm wine) was used to strengthen the colours. The artists who decorated the house were traditionally paid with buffalo. The majority of the carvings on Toraja houses and granaries signify prosperity and fertility, and the motifs used are those important to the owner's family. Circular motifs represent the sun, the symbol of power, a golden keris (knife) symbolizes wealth and buffalo heads stand for prosperity and ritual sacrifice. Many of the designs are associated with water, which in itself symbolizes life, fertility and prolific rice fields. Tadpoles and water-weeds, both of which breed rapidly, represent hopes for many children. Many of the motifs that adorn the houses and granaries of the Toraja are identical to those found on the bronze kettle drums of the Dong-Son. Others, such as the square cross motif, are thought to have Hindu-Buddhist origins or to have been copied from Indian trade cloths. The cross is used by the Christian Toraja as a decorative design emblematic of their faith. On the front wall of the most important houses of origin is mounted a realistically carved wooden buffalo head, adorned with actual horns. This emblem may only be added to the house after one of the most important funeral rites has been celebrated.

To the Toraja, the tongkonan is more than just a structure. The symbol of family identity and tradition, representing all the descendants of a founding ancestor, it is the focus of ritual life. It forms the most important nexus within the web of kinship. Toraja's may have difficulty defining their exact relationship to distant kind, but can always name the natal houses of parents, grandparents and sometimes distant ancestors, for they consider themselves to be related through these houses. Descent amongst the Toraja is traced bilaterally - that is, through both the male and female line. People therefore belong to more than one house. Membership of these houses only requires the kinsman's active participation at times of ceremony, the division of an inheritance or when a house is rebuilt. Although the tongkonan has become identified by outsiders as being representative of all Toraja buildings, it is only the nobility and their descendants who can afford both the building of the houses themselves and the enormous ritual feasts associated with them. Noble Toraja can claim affiliation to a particular tongkonan as descendants of the founding ancestor, through the male or female line. This association is periodically confirmed through contributions to the ceremonial feasts given by the tongkonan household. Commoners customarily lived in smaller, simpler houses and acted as helpers at these communal feasts. Commoners trace their descent through their own houses of origin. These, although of simpler design and decoration, may still be known as tongkonan. As in so many places in modern Indonesia, the traditional house, with its cramped, dark, smoky interior, has lost its attraction for many Toraja (although it still commands great ritual prestige). Many have opted for a ground-built, concrete, single-storey house in the contemporary Pan-Indonesian style, and some have adopted a wooden, pile-built dwelling. Others who are more inclined towards tradition may add an extra storey and a saddleback roof; this provides more living space and room for furniture whilst retaining something of the prestige the tongkonan affords its owner. Contemporary Toraja buildings are thus the result of architectonic development which has diminished their value as dwellings. In so doing, they have employed new technology to further emphasize the traditional philosophy of the Toraja. The basic plan has remained virtually constant throughout the changes, and the importance of its underlying notions of culture, religion, and society has guided the direction of the tongkonan's evolvement. So close have the lines of change stayed to these fundamental concepts, that the process has been labeled an "involution". Despite the modernity of the new tongkonan, it has succeeded in maintaining its richness of intertwined symbolism and continues to resonate with deep cultural meaning.

0 comments:

Post a Comment